Exploring Orchestral Music: Race and Gender Representation of Composers

Introduction

In thinking about creative ways that people can explore orchestral music and find new pieces that they like, I’ve been thinking a lot about representation. There are many good pieces written by composers who don’t fit the stereotype of dead white men, and I want to make sure they are prominently featured in my posts.

In some cases, this means exploring the work of living composers, since opportunities for women composers and composers of colour are marginally better now than in previous centuries. In other cases, it means exploring composers from history who are recently being “rediscovered”. Sometimes the rediscovery is literal, as in the case of Florence Price’s fourth symphony, written in 1945, where the manuscript was found in 2009 during a renovation of what used to be her summer home 1. Other times, the rediscovery is more of a re-examination, such as appreciating Clara Schumann as a talented composer and performer in her own right, and not just a footnote to her husband’s legacy 2.

Thinking about race and gender representation is an interesting way to look at music, but it also leads us into other interesting trains of thought. Exploring new music naturally leads us to thinking about the curators—visible and invisible—that select music, promote it, and make it easy to find. It’s also an interesting way to think about the tension between honouring the past and pushing for the future; to what extent orchestras should spend their time acting as a living museum versus playing the work of artists on the vanguard.

Ultimately, I hope that highlighting diverse composers for people who want to get into orchestral music helps to cement change. Familiarity is essential to enjoyment and mass appeal, as noted in the 2019 book Rockonomics:

“[T]here is a tendency for music that is popular in our networks to become more appealing to us. And bandwagon effects are further reinforced by the well-established psychological tendency for people to grow to like a particular song the more they hear it.” 3

Hopefully, the more that people discover, listen to, and enjoy the work of composers who are people of colour, women, or both, the more that these composers will be given their rightful stature in the “canon” of orchestral music.

Research on composer representation in orchestra seasons

In addition to some of my own research, I have been looking at existing research that has been done on the representation of composers within orchestra seasons (primarily for orchestras in the United States). I’ve included a list at the end of this post as an appendix.

Most of these analyses highlight the lack of women composers, composers of colour, or both, who are programmed in orchestra seasons. The good news is that some progress is being made — for example, among the biggest US orchestras, representation of women composers has more than tripled in the last five years (more on this later). However, there is still a long way to go — the 2019/20 season analysis of 120 US orchestras from the Institute for Composer Diversity found that only 8% of works performed were by women composers, and only 6% were by composers from underrepresented racial, ethnic, or cultural heritages.

Not just who: also how

To complement the quantitative information from the various season analyses mentioned above, I want to introduce two other interesting ways to dig deeper into how composers are represented in orchestra programs:

Duration and placement

The most common format for an orchestral concert looks something like this:

- A short feature piece, maybe about 10-15 minutes long

- A medium-length piece, usually a concerto 4 or a short symphony

- A long piece, usually a symphony or some other multi-movement work

You can see this pretty clearly in the format of MasterWorks 5 concerts from the TSO’s last season:

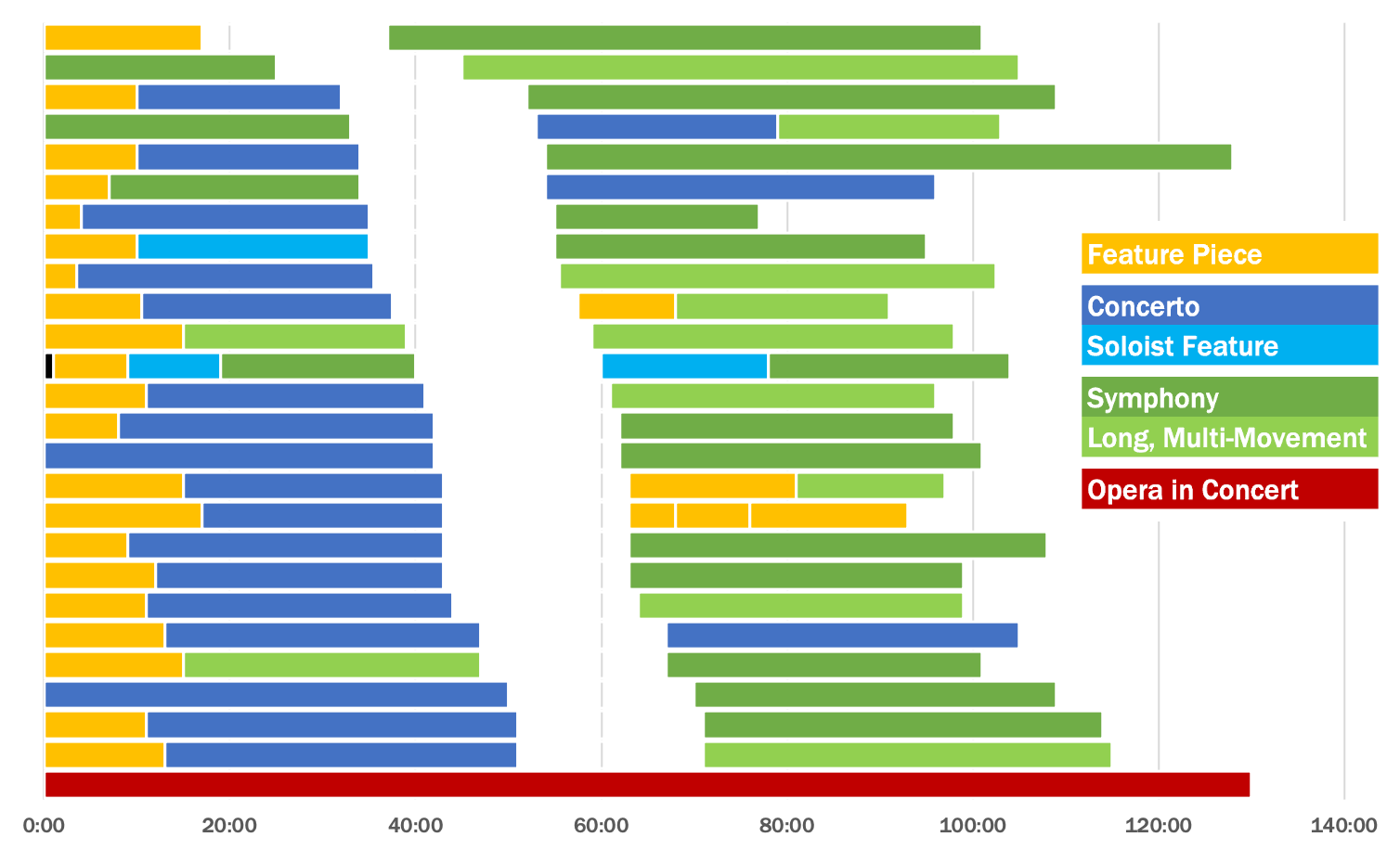

A visual summary of the duration 6 and placement of pieces in TSO MasterWorks concerts planned for the 2019/20 season. Rows represent individual concert programs, with each piece colour-coded by type. The large uncoloured gaps represent intermissions. Concerts have been ordered by onset of intermission for visual clarity 7.

Most of the time, pieces by living composers get put into the “short feature piece” slot. I’m don’t know for sure why this is, so I can only speculate. Maybe this is because writing or commissioning new music for orchestra involves a lot of expense and effort, so long pieces written by living composers are rarer. Another potential reason is the fact that orchestra concerts themselves are expensive to produce, so it’s risky to bet your biggest piece on something audiences don’t already know and love.

A slightly more cynical take would be that, for some people, new music has a reputation of being hard to listen to, so keeping it short and early in the program makes concerts tolerable for audience members who don’t like abstract or atonal music that much. The Baltimore Symphony has a good blog post about the reputation that “new music” has with audiences.

In any case, it’s notable when works by a composer of colour, or a woman composer (or honestly, a living composer) takes the longest spot on the program. In fact, the Institute for Composer Diversity specifically makes a point of recommending that Orchestras “Include more substantial works by composers from underrepresented groups in the second or third positions on the program.”

Representation in marketing materials

Marketing focus is also an interesting way to think about programming, and is reflected in the title of a concert program, its description, and the images used to sell it. My guess is that in most orchestras, the names and descriptions for concert programs are primarily written by the marketing department, with some input from the artistic staff.

Concerts are most commonly named after the most well-known piece on the program, the featured soloist or conductor, or some combination of both. It’s very rare for a concert program title to be based on a living composer, unless it’s a Pops Concert (e.g. “Music of John Williams”). It’s notable when this occasionally happens, since it signifies an intentional artistic decision or that the living composer is popular enough that their name will sell tickets.

Women’s Philharmonic Advocacy had some good notes on this subject in their 2017/18 season analysis:

It is worth noting that even though these works are being performed, they are not necessarily being recognized or promoted. There were disturbingly few mentions of works by women in the online or print descriptions of each concert, even when the included work was commissioned. For example, the Seattle Symphony has included Lili Boulanger’s D’un matin de printemps for a program titled Rachmaninov Symphony No. 3, taking place in February. The other works on the program include Elgar’s Violin Concerto and, of course, the Rachmaninov Symphony. The description for the event, however, only mentions two of the three[.]

As you may have guessed, Boulanger’s piece is the one out of the three not mentioned in the concert description—and this is only one out of four examples WPA included of women composers being ignored in marketing materials. (I would highly encourage you to go read the whole post - it’s very good.)

Up next: streaming services and their classical playlists

At some point I want to explore to the various season analyses that are linked below. Before that (in the next post), I’m going to use some of my own research to take a look at representation in some of the biggest classical and orchestral playlists from Spotify and Apple Music.

Spoiler alert: it’s not great.

Appendix: analyses of orchestra seasons

Updated and Expanded Version of This List

I’ve since expanded this list into its own page with additional studies and commentary. You can view the expanded version of this list here.

The Baltimore Symphony Orchestra had a series called “By the Numbers” analyzing the concert seasons of top US orchestras:

- Baltimore 2014/15 (22 Orchestras)

- Baltimore 2015/16 (89 Orchestras)

- Baltimore 2016/17 (85 Orchestras)

The Baltimore series stopped after three seasons, but Women’s Philharmonic Advocacy started doing their own season analysis starting in 2016/17 with a smaller list of 21 orchestras 8 I think the intention was to continue using the 21 orchestras that Baltimore had initially looked at for 2014/15, though Baltimore later added Nashville, bringing their 2014/15 number up to 22. as a way to highlight the lack of women composers represented in orchestra programs:

Another organization, called DONNE, has been doing similar analysis for a more global set of 15 orchestras:

DONNE also has a research page with links to other studies on representation in music, including one on (mostly-classical) French music festivals, which I have put on my reading list.

Most recently, the Institute for Composer Diversity was founded within the School of Music at the State University of New York at Fredonia. They published an analysis of Orchestra Seasons for 2019/20 that includes data from 120 orchestras. Their analysis looks at representation of composers from underrepresented racial, ethnic, or cultural heritages in addition to gender.

-

See: New Yorker Magazine: “The Rediscovery of Florence Price” ↩

-

See: New York Times: “Clara Schumann, Music’s Unsung Renaissance Woman” ↩

-

Krueger, Alan B. Rockonomics: A Backstage Tour of What the Music Industry Can Teach Us about Economics and Life. Broadway Business, 2019.

The author cites two research papers for the last quoted sentence, which I have listed below:

David J. Hargreaves, “The Effects of Repetition on Liking for Music,” Journal of Research in Music Education 32, no. 1 (1984): 35–47 (No public PDF link, but you should be able to get a copy if your local library has access to JSTOR.)

Robert B. Zajonc, “Attitudinal Effects of Mere Exposure,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 9, no. 2, pt. 2 (1968): 1–27. (Link to PDF) ↩

-

A concerto is a piece of music that showcases a soloist, e.g. a pianist or violinist. ↩

-

The TSO’s MasterWorks series is what you might call the orchestra’s “core classical” program. The TSO also has pops concerts, school and youth concerts, film concerts, and other special events. Most of the season analyses I’ve linked to in the appendix only focus on core classical concerts for artistic and logistical reasons. ↩

-

It’s interesting to note that the median total length of pieces + intermission for these programs is about 100 minutes, which is very close to the average movie runtime in recent decades (For more on movies, see this interesting analysis of movie runtimes done by Przemysław Jarząbek on the Toward Data Science blog.) In reality, I would guess the median concert runtime is probably about 110 minutes due to stage resets between pieces, introductions, etc. ↩

-

Source: Concert programs for 2019/20 Toronto Symphony Orchestra MasterWorks concerts. Due to COVID-19, not all of these concerts actually happened—about a third of them were cancelled. ↩