Deep Dive: Composer Representation in Spotify Classical Playlists (Part Three)

This article is Part 5 in the Classical Playlists on Spotify and Apple Music series.

Music For Every Mood

Continuing from the previous post on Spotify’s all-orchestra playlist, we’re now turning back to the calm and digression-worthy world of mood playlists with a look at Spotify’s Classical Sleep.

Classical Sleep

| Classical Sleep | If Average US Orchestra | |

|---|---|---|

| Tracks | 72 | |

| Women | 3 (4.2%) | 6 |

| Black | 2 (2.8%) | 4 |

| Women of Colour | 0 | 1 |

| Living | 36 (50%) | 12 |

Compared to Apple Music’s Relaxing Classical, this mood-themed playlist has representation of at least one composer of colour with the two pieces by Alexis Ffrench, and one more piece by a female composer.

However, the two mood-themed playlists are wildly different when it comes to living composers, because they seem to have very different programming approaches. Apple Music’s Relaxing Classical takes the existing “canon” and selects mood-appropriate pieces from within it. Pieces by Beethoven, Mozart, Brahms, Debussy, and Rachmaninoff make up nearly half of the playlist. As a result, only two of the tracks featured are by living composers.

Spotify’s Classical Sleep, on the other hand, has 36 tracks by living composers, half of the overall total. This is because “Classical” in Spotify’s parlance means a mix of mood-appropriate pieces from the “canon” alongside modern artists who make mood music using classical instruments.

The living composers responsible for those 36 tracks range from often-anonymous artists, 1 whose entire career is designed around providing the kind of algorithmically-friendly music favoured by mood playlists, to artists like Elena Kats-Chernin, who frequently work with orchestras.

Alexis Ffrench: Together At Last; Bluebird

Alexis Ffrench (born 1970) is a British classical soul pioneer, composer, producer and pianist. Not only is Ffrench the UK’s biggest selling pianist of 2020, he has headlined London’s Royal Albert Hall, collaborated with fashion houses Miyake and Hugo Boss, played Latitude Festival, worked with Paloma Faith, composed several film scores and shares the same management team as Little Mix and Niall Horan.

Appearance #2 for Ffrench, whose A Time for Giving was featured on Apple Music’s The A-List: Classical. The first of these two songs, Together At Last, is the titular song from Ffrench’s 2018 holiday EP. Like A Time for Giving, which is from Ffrench’s 2020 holiday EP, Home, it reminds me of the church music influences that Ffrench has spoken about in his music.

The second, Bluebird, is far and away Ffrench’s most popular song, and in my comments about the Apple Music playlist, I linked to a great performance of it from the BRIT awards. It reminds me in so many good ways of Married Life from Michael Giacchino’s soundtrack to UP — the sighing phrases, the gentle piano, the sense of time looping and passing at the same time. It’s really excellent. 2

Amy Beach: Berceuse (Lullaby), No. 2 from Three Compositions, Op. 40

Amy Marcy Cheney Beach (September 5, 1867 – December 27, 1944) was an American composer and pianist. She was the first successful American female composer of large-scale art music. Her “Gaelic” Symphony, premiered by the Boston Symphony Orchestra in 1896, was the first symphony composed and published by an American woman. She was one of the first American composers to succeed without the benefit of European training, and one of the most respected and acclaimed American composers of her era. As a pianist, she was acclaimed for concerts she gave featuring her own music in the United States and in Germany.

Another second appearance: Beach’s Young Birches, Op. 128 were featured on Spotify’s Classical Essentials. The song title doesn’t really make it clear (the track in the playlist is from a lullaby compilation album), but this is the second movement from a trio, which you can listen to on this album from the Klugherz-Timmons Duo.

Nadje Noordhuis: Bluebird

Described as “one of the most compelling voices to emerge on her instrument in recent years” (Dan Bilawksy, All about Jazz), Australian-born New York based trumpeter/composer Nadje Noordhuis possesses one of the most unforgettably lyrical voices in modern music. Her deeply-felt, clarion tone and evocative compositional gift meld classical rigor, jazz expression, and world music accents into a sound that is distinctively her own. (Personal Website Biography)

Our second song called Bluebird on this playlist. One interesting thing they both have in common is that the piano is mic’d in such a way that you can hear the sounds of the sustain pedal and other moving parts click and thud in the background. It’s an interesting feature of the lo-fi production you can find on many mood-themed playlists.

Of course, the real jewel of this track is the trumpet performance. Noordhuis plays with a lovely warm tone and is able to effortlessly glide into and out of silence in certain phrases. If you like this track, I’d recommend you check out the whole album, which is titled Ten Sails.

A Digression About Metadata

The other interesting thing about this song is that it illustrates an issue that has been frequently discussed about Spotify and other streaming platforms. At a high level, a song has two sets of rights, which result in two types of revenue streams. First, there is the “master” right to the recording itself, and second, there are the “publishing” rights for the music composition. When you stream a track on Apple Music or Spotify, both sets of rightsholders need to be paid. However, especially for publishing rightsholders (e.g. a composer or songwriter), the data that tells the streaming service who to pay is often missing.

This is a huge problem. In a recent review, the UK Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Committee heard that there are billions of dollars unallocated due to bad data:

At best, mismatched, incomplete or missing metadata can result in delays to creator royalties for months or even years. At worst, this can result in payments being misallocated or otherwise consigned as unclaimed or non-attributable royalties to ‘black boxes’. Black boxes consisted of $2.5 billion in unallocated income in 2019 alone. 3

Sometimes, artists are able to get the data fixed and collect the income they are entitled to. However, the committee heard that most of the money goes elsewhere:

After a period of time, black boxes are then assigned pro-rata to streams that have been correctly identified, which is established in standard publishing agreements. This means that those creators and companies, particularly who are most listened to, are effectively are [sic] paid twice: first for their own streams, and then for streams that cannot be allocated. 4

There are many reasons this problem persists, including the need to digitize paper records for back catalogues, and limitations on who can submit corrections or challenges to bad data. However, a big part of the problem is lack of effort from record labels:

Because the recording and song rights are licensed separately and often held by different music creators and companies, many labels do not supply the relevant ISWC 5 when licensing music to streaming services, meaning that songwriters often lose out altogether when music is streamed. Often, this is by choice because of the difficulty of doing so: in oral evidence, Maria Forte asserted that in conversation with one record label, a representative said “‘I don’t care about composer information because it’s nothing to do with me. I’m not changing my system to do that’”. 6

In essence, there is a mismatch of responsibility and incentive. The record label earns its income from owning the master rights to a song. However, it is responsible for supplying the data that identifies the master rights holder(s) and the publishing rights holder(s) when the song is uploaded. As a result, the master rights data is usually correct, but the publishing rights data is often incorrect or omitted, unless the record label has a financial stake in ensuring the publishing rights data is correct.

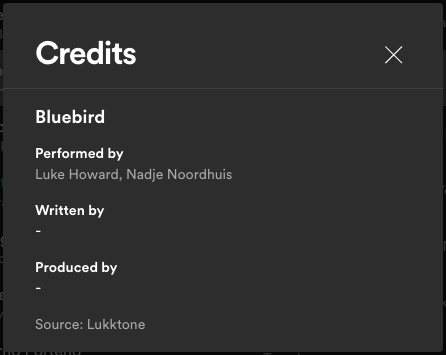

Bluebird is an excellent example of this — when the song was originally uploaded to Spotify, the songwriter credit for Nadje Noordhuis was missing:

However, at the time, songwriter credits for Nadje’s collaborator, Luke Howard, were included on the same album. The label, Lukktone, appears to be owned or controlled by Luke Howard (since all of its releases feature him as an artist). I’m not accusing anyone here of malice — it just illustrates the broader issue: Lukktone had a strong financial incentive to ensure that the songwriter credits for Luke Howard were correctly submitted; it had less of an incentive to ensure that the credits for Nadje Noordhuis were also correct.

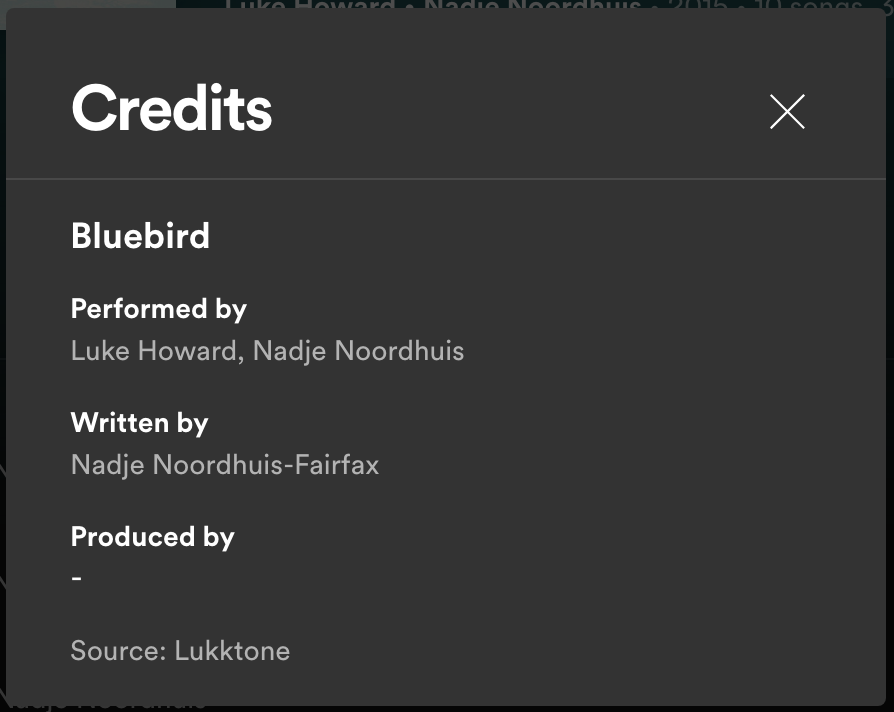

Fortunately, this particular story has a positive ending. At some point between September and October 2021, the credits were corrected:

Even still, this album was released in 2015, which means that at best, Nadja Noordhuis will be receiving a couple thousand dollars in publishing revenue 7 for a song that’s been streamed over 4 million times on Spotify — six years late.

If you’re interested in reading more about this issue, you can check out a good article from The Verge from a couple years ago as well as the full discussion of the issue in the UK Parliament Report (starting on the page numbered 49/page 53 in the PDF). (Full materials from the UK committee review).

Elena Kats-Chernin: Lullaby For Nick

Elena Kats-Chernin AO (born 4 November 1957) is a Soviet-born Australian pianist and composer, best known for her ballet Wild Swans.

I think I would describe the vibe of this song as “Pull up a chair and get comfortable. I’m about to tell you a long story, starting from the beginning.” Perhaps I should have suggested you listen to this before the metadata digression above. If I had a piano in my house, I would definitely learn how to play this; if you want to learn how to play it, you can buy the sheet music from Boosey & Hawkes.

Up Next

In the next post in this series, I’ll finish off the Spotify deep dive with a look at their Classical New Releases playlist.

Playlist, Methodology, and Data

You can listen to all of the pieces featured in this playlist analysis series here: Spotify: Classical Deep Dive - Spotify & Apple Music.

Full methodology notes for all my music posts can be found via the Main Methodology Page.

Details and data for the streaming service playlists analysis can be found on the Streaming Analysis Methodology Page.

More details about how I used the data from the Institute for Composer Diversity to create the comparison to US orchestra mainstage seasons can be found on the ICD 2019/20 Season Analysis Methodology Page.

-

If you look at the data for this project, you’ll see “No Sources Found” for the demographic attributes of artists that could not be linked to a known person. The methodology page also has notes on how unknown artists were handled in the analysis. ↩

-

To make sure, I went to listen to Married Life again, and this has tangentially inspired me with a business idea for orchestras:

Nearly everyone who has seen UP will be unable to listen to Married Life without being brought to tears, or at least this is my personal experience. It’s a masterpiece of modern cinema, packing an incredible amount of emotional affect into a very short number of minutes.

Now, the last time I went to see a Pops program about film scores, Married Life was not on it, which is surely a crime, but also an incredible missed opportunity. Much like you can shore up a financially deficient theme park in Rollercoaster Tycoon by jacking up the price of umbrellas when it rains, every orchestra should put Married Life just before intermission and then have the ushers sell packets of tissues for $5 each on the way out to the lobby.

OK, OK, so in the current context of there still very much being a global pandemic, maybe encouraging everyone to nose trumpet for revenue is a bad idea health-wise. But when COVID-19 is finally over and dead in the ground (dear lord, one day soon I hope), this is the path back to financial stability that all orchestras should surely take.

Anyway, my point is that Bluebird is a really good song. ↩

-

Paragraph 93, page 51. Sources in original.

Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Committee. “Economics of Music Streaming: Second Report of Session 2021–22.” London, United Kingdom: House of Commons, July 9, 2021. https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/6739/documents/72525/default/.

The original source for the $2.5 billion figure was a 2017 article by Digital Music News which cited figures provided by Paperchain, a tech company. ↩

-

Paragraph 93, page 51. Sources in original.

Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Committee. “Economics of Music Streaming: Second Report of Session 2021–22.” London, United Kingdom: House of Commons, July 9, 2021. https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/6739/documents/72525/default/. ↩

-

International Standard Musical Works Code, a unique identifier used to help identify the correct rightsholders. ↩

-

Paragraph 90, page 50. Sources in original.

Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Committee. “Economics of Music Streaming: Second Report of Session 2021–22.” London, United Kingdom: House of Commons, July 9, 2021. https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/6739/documents/72525/default/. ↩

-

It’s hard to estimate exactly, but you could extrapolate from the average master right payout and take a guess at what the publishing revenue might be:

USD $0.004 per-stream master right payment × (15% publishing / 55% master) × 4,200,000 streams × 50% revenue share with publisher ≈ $2,300 ↩

Articles in the Classical Playlists on Spotify and Apple Music series:

- Part 1 - Representation of Composers in Top Classical Playlists on Spotify and Apple Music

- Part 2 - Deep Dive: Composer Representation in Apple Music Classical Playlists

- Part 3 - Deep Dive: Composer Representation in Spotify Classical Playlists (Part One)

- Part 4 - Deep Dive: Composer Representation in Spotify Classical Playlists (Part Two)

- Part 5 - Deep Dive: Composer Representation in Spotify Classical Playlists (Part Three) (Current Page)

- Part 6 - Deep Dive: Composer Representation in Spotify Classical Playlists (Part Four)