Steps to Writing a Grant: Part I

This article is Part 2 in the Grant Portal Limitations series.

In the intro post I argued that grant portals are rarely designed to make life easier for the grant writer. But what if they were? There is a whole list of things that a grant writer has to do before they press “submit”, and grant portals can help or hinder that work at various points along the way.

If you’re looking for a broader overview of grants for non-profits and charities, I would highly recommend this “grants 101” article from Imagine Canada.

I’m going to describe the steps that most grant writing projects go through. Along the way, we can imagine how portals could make grant writing easier, and then we’ll take a look at the reality of how they mostly don’t.

Here are the steps:

1. Discover the funding program

To state the obvious, you have to know a funding program exists in order to apply for it. Funders usually advertise and describe their funding programs on their website. However, this is a difficult task, because they have to communicate lots of different things to different people. Eligibility, for example, varies by artistic discipline and organization type, but most grant writers want to be able to quickly drill down to the programs that are meant for them or their organization.

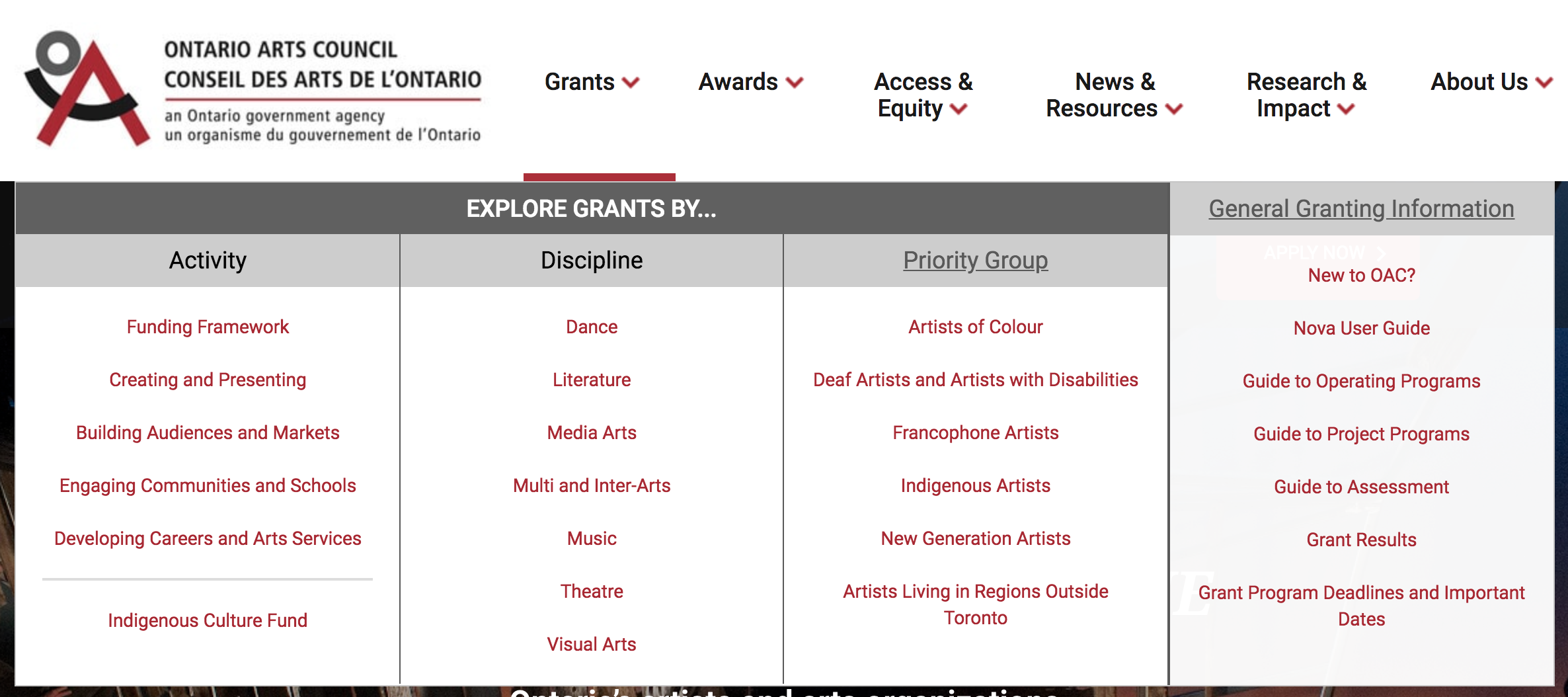

Most organizations try to help with this by designing their websites with detailed menus to help you find relevant programs. See, for example, the website menu for the Ontario Arts Council (OAC):

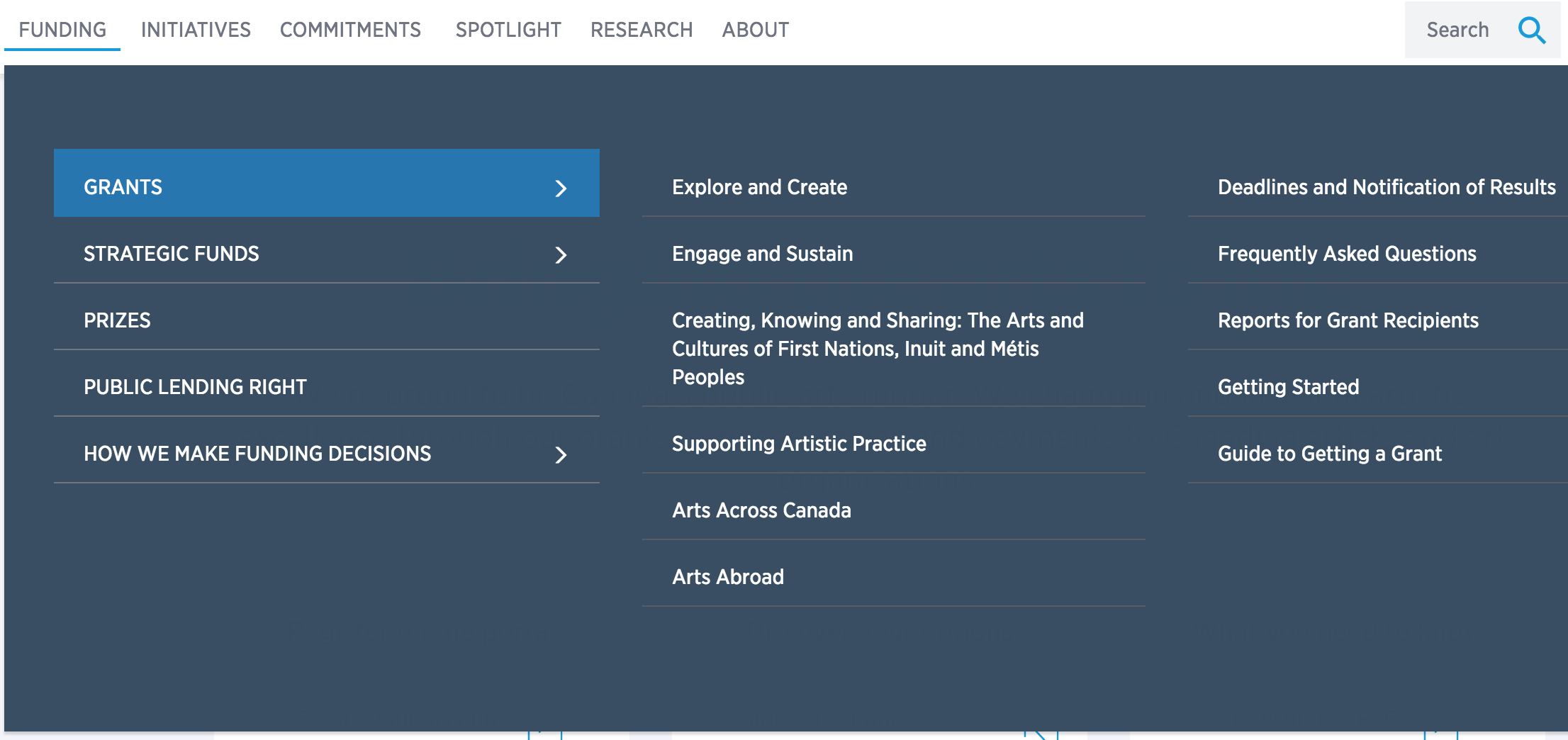

Or the less helpful website menu for the Canada Council for the Arts (CCA):

Grant portals should have an advantage here—to use a grant portal, you usually have to create a detailed profile for you or your organization. This means that the portal should already know who you are and what programs you are eligible for.

Some organizations, such as the Canada Council for the Arts, do take advantage of this and provide a customized list of available funding programs within their portals. Others, such as the Ontario Arts Council seemingly do not. (For example, in my OAC account registered to an incorporated non-profit, it lists the Exhibition Assistance program which explicitly does not fund non-profit corporations.)

Given how much a portal already knows about you, there is a lot of potential here, but it is mostly untapped. For example, most portals do not send you emails when deadlines for eligible programs are coming up, meaning that even if a portal did the work of showing you eligible programs, you would still have to log in to see it.

In a lot of ways, it makes sense that the potential here is ignored. Most grant writers only visit the portal when they are going to write a grant, so unless you can send customized emails, the effort would probably go un-seen. Funders might also assume that most people who have gone to the trouble of setting up a portal account are probably familiar enough with their funding programs to know which ones they are eligible for. We’ll come back to that assumption later.

2. Find out more about the program

So you’ve found a program you can apply to. Is it worth it to write an application? Part of being a good grant writer is being strategic about where you commit your time and the time of other people in your organization.

Grant writers are fundraisers, and over the course of a year they have to try to pick applications that strike a balance between getting the most funding possible and getting dependable funding that will help them meet their revenue budget. If there’s only a 10% chance an application will be successful or if it only offers a small amount of money for the time invested, it’s probably not worth the effort.

More importantly, grants are dangerous, because they almost always come with obligations. Picking the wrong grant could make an organization’s finances worse–for example, if a grant only funds 50% of a project’s costs, and taking it forces you to spend the other 50% from money your organization doesn’t have. The wrong grant could also contribute to mission creep, forcing your organization to work on projects that are outside its core purpose.

To weigh all these factors, a grant writer needs to be able to answer a lot of questions about a funding program. What kinds of projects and expenses will it fund? How much funding will it offer in total? What are the obligations and work that would come with taking the funding? How long will it take to put together a good application?

That last question can be quite tricky to answer. I’ve seen some portals where you can’t see what the application form looks like until quite close to the deadline. This often happens because you’re waiting for your registration to be approved, or because the funder only makes one type of application “live” in the portal at a time.

Usually funders are nice and will hide provide a PDF of the application questions on their website, though these don’t always give you all the little details, like whether you can put descriptions on supporting material, or if you just have to rely on writing meaningful file names. For some reason, information like “estimated writing time”, “total question word count”, and “list of appendices required” is usually not summarized for you, so you have to make your own summary to figure out how much work it’s going to take to apply.

3. Decide to apply

Once all your questions about the funding program have been answered, the grant writer can decide whether an application is worth their time. More importantly, anyone else who would be affected needs to decide that it’s worth their time too. This needs to be a real decision—the kind where everyone is committed to whatever is promised in the application, including the worst and best possible scenarios.

This has nothing to do with grant portals. It’s just a super important part of grant writing and I wanted to mention it.

That’s a lot of work already, and we haven’t even gotten to the writing part. In fact, if I were going to hire a grantwriter, I wouldn’t ask them for a writing sample from an application. I would ask them to write a one-page briefing for program staff about a funding program, the kind of document you would write up for step #3.

The writing part does come next though, and I’ll go through that… in the next post.

Articles in the Grant Portal Limitations series:

- Part 1 - Grant Portal Limitations - Intro

- Part 2 - Steps to Writing a Grant: Part I (Current Page)

- Part 3 - Steps to Writing A Grant: Part II

- Part 4 - Formatting Restrictions in Grant Portals